The Performance of Depth

Somewhere along the way, thinking became something we perform.

We used to read books quietly, write notes in the margins, and let ideas ferment unseen. Now, the moment we encounter something profound, we turn it into content - a highlight, a thread, a screenshot. We package thought into something postable.

The private act of reflection has become a public signal.

Our desire to show others our lives has grown greater than our desire to live them. As Daniel Kahneman once wrote:

“The Instagram generation experiences the present moment as an anticipated memory.” (h/t Gurwinder Bhogal.)

We no longer simply read or think. We anticipate the moment others will see that we’re doing it.

i. the aesthetic of intellect

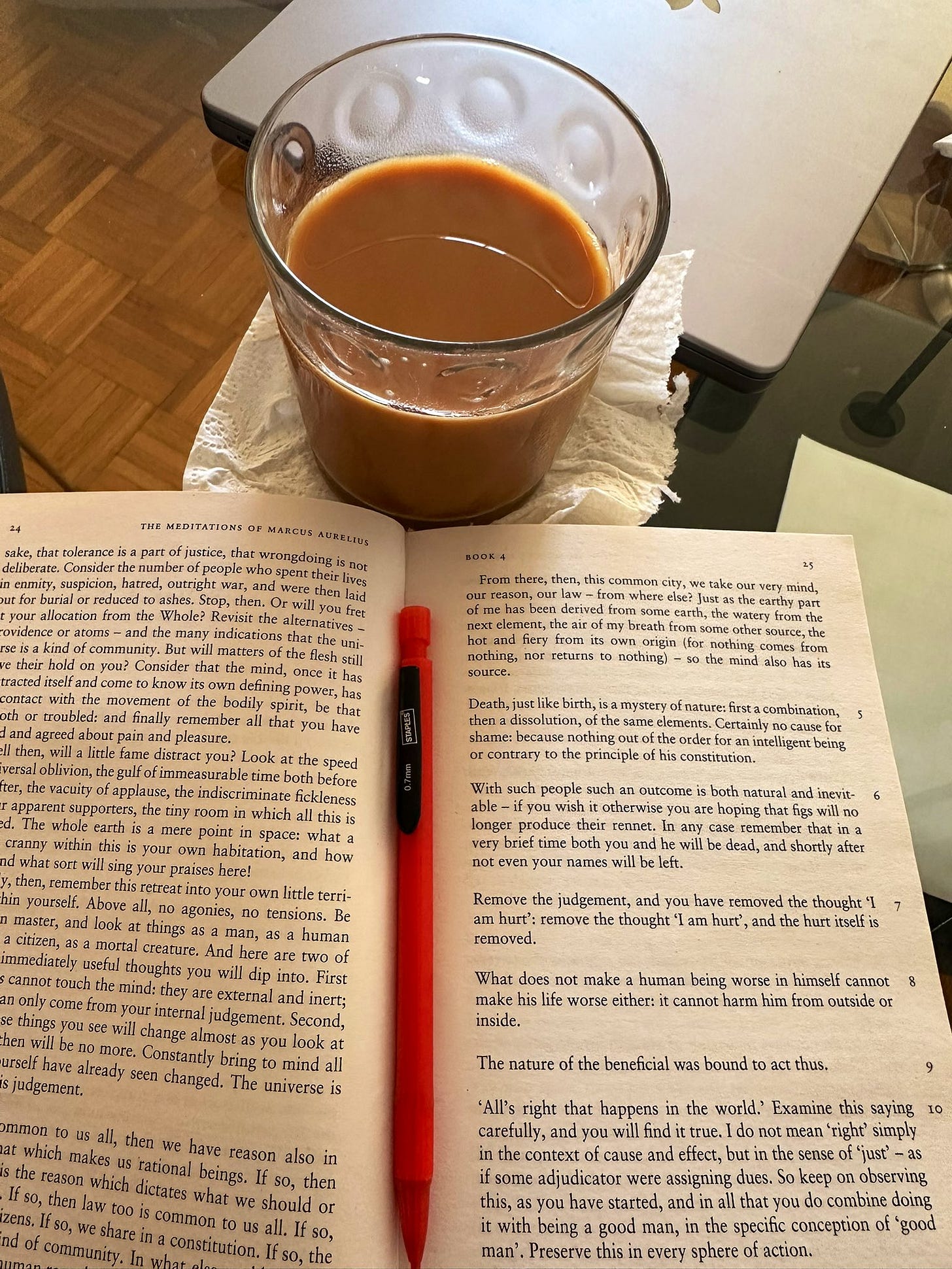

Scroll through social media and you’ll find the visual grammar of modern thought: a black coffee beside a Moleskine, Meditations cracked open at just the right page, a MacBook glowing with an essay draft in serif font.

It’s not deceitful, the person is reading, is thinking. But it’s also a form of branding. The image isn’t just proof of activity; it’s proof of identity. It says: I am thoughtful, disciplined, curious, one of the good ones.

We’ve built an aesthetic of intellect, a kind of “mind minimalism” where even our curiosity must look clean. The messy, private, slow work of learning has been replaced by its photogenic outline.

Sociologist Erving Goffman called this impression management, our instinct to perform versions of ourselves for others. But in the internet age, that instinct has been industrialized. We no longer perform depth occasionally; we live inside that performance.

ii. depth as display

In the same way that fitness influencers document their workouts, thinkers now document their attention. The morning routines, journaling habits, book stacks, and quote dumps, these are the new intellectual equivalents of gym selfies.

It’s not about vanity; it’s about belonging. Each post reassures us that we’re still part of the conversation, still “keeping up” with the thinkers we admire. But the moment thinking becomes public-facing, it begins to deform. The question shifts from What do I really believe? to What looks intelligent?

The market for looking intelligent is vast. Stoic quotes, Nietzsche fragments, Zen aphorisms, pre-digested pieces of wisdom that fit neatly into squares and carousels. The algorithms reward recognizability over originality, clarity over confusion.

And so, what we call “depth” online is often the absence of resistance. The most popular ideas are the ones that ask nothing of you.

iii. the illusion of learning

We’ve all done it: highlighted a brilliant line on Kindle, saved it to Readwise, felt a little jolt of satisfaction, as though the act of collecting wisdom were the same as understanding it.

But understanding is slow, and the modern mind is optimized for speed.

Cognitive psychologists describe this as the illusion of explanatory depth, our tendency to believe we understand something deeply until we’re asked to explain it. You can quote Seneca all day, but the moment someone asks what he meant, you realize how thin your comprehension really is.

The internet amplifies that illusion. We have thousands of notes, highlights, and snippets, a fossil record of thoughts we never fully absorbed. We confuse possession of ideas with possession by ideas.

Saving replaces sitting. Consumption replaces contemplation.

We are surrounded by wisdom, but starved of integration.

iv. knowledge as belonging

Underneath it all is something deeply human: the need to belong.

We join intellectual tribes the way our ancestors joined villages, through shared symbols, heroes, and language. The productivity tribe has its tools: Roam, Obsidian, second-brain diagrams. The philosophy tribe has its canon: Marcus, Seneca, Naval, Nietzsche. The rationalists have their own dialect of Bayesian precision.

Each group is comforting because it offers a map of meaning, and a shortcut to identity. But tribal thinking comes at a cost: it prizes familiarity over truth.

Quote Seneca, and you’re applauded. Misinterpret him in an original way, and you’re ignored.

The irony is that we form these communities to think, but end up thinking less. We start to curate beliefs the way we curate playlists, chosen for mood, not for accuracy.

Depth, once a measure of inner transformation, becomes a badge of cultural affiliation.

v. the attention economy and the poverty of thought

In 1969, Herbert Simon foresaw this:

“A wealth of information creates a poverty of attention.”

Today that poverty is our default condition. Every moment is a competition for mental bandwidth, podcasts, newsletters, threads, summaries, thinkpieces. We treat attention like a muscle to be constantly exercised, not a space to be occasionally emptied.

But thinking requires emptiness. It requires boredom, confusion, stillness, moments where your brain isn’t optimizing for output. Real thought doesn’t happen when you’re consuming; it happens when you’re stuck.

Marcus Aurelius wrote Meditations not as a book, but as a private exercise, a series of nightly notes to himself while he was at war, ruling an empire, and watching people he loved die. There were no readers in mind, no audience, no performance. Just a man trying to reason his way through chaos.

He’d write in tents, on campaign, in the quiet after battle, reminders to stay calm, to accept what he couldn’t control, to live with virtue. The sentences are short because he was speaking to himself.

That’s why Meditations endures. It isn’t a book written for others; it’s a record of someone thinking alone.

The internet gives us information faster than we can metabolize it. And because friction doesn’t photograph well, we skip digestion entirely. We distribute before we understand. We share before we’ve sat with it. We perform thought before we’ve proven it.

vi. the cost of private thought

That’s what Proof of Thought means to me.

In crypto, proof of work ensures that every coin represents effort, time, energy, computation. Thought works the same way. An idea only becomes yours after you’ve paid for it, with attention, confusion, and risk.

If you never misunderstood an idea, never wrestled with it, never felt it rearranging your worldview, then it isn’t yours yet. It’s someone else’s thought wearing your voice.

Real thinking is costly precisely because it’s lonely. There’s no applause in the middle of a paragraph you don’t understand. There’s no validation in rereading a dense page until it finally clicks. But those invisible moments, the ones no one sees, are where wisdom takes root.

We’re so used to proof of audience that we’ve forgotten the value of proof of effort.

vii. a quiet rebellion

So maybe the solution isn’t to log off, but to slow down.

To read something and not highlight it. To resist the urge to summarize or share. To let ideas ferment quietly until they stop sounding borrowed.

Think privately.

Share selectively.

Let some thoughts stay unpolished long enough to grow patina — the intellectual kind that comes from time and use, not filters and fonts.

My last essay was about learning to let objects age, then The Performance of Depth is about letting ideas age, to let them bruise and breathe until they belong to you.

Because proof of thought is not how fast you can express an idea, but how long you’re willing to live with it.

References & Inspirations

Daniel Kahneman & Amos Tversky — Prospect Theory; the psychology of perception and recall.

Herbert Simon — “Designing Organizations for an Information-Rich World” (1969).

Erving Goffman — The Presentation of Self in Everyday Life.

Illusion of Explanatory Depth — Rozenblit & Keil, Yale University (2002).

Gurwinder Bhogal — essays on simulated wisdom and performative intellect.

Naval Ravikant — “Play long-term games with long-term people.” (A line that, ironically, can only be lived, not posted.)

as you mentioned in the 'illusion of learning' section of the essay, I also found myself racing to hoard ideas that weren't mine when I first began reading. I'd read an essay on psyche and force myself to remember the name of a phenomenon, I'd read a piece related to nutrition and then murmur the name of particular hormone to memorize it, simultaneously envisioning myself to use the term in future. And when the future did arrive, I found myself with zero memory or even recognition of the things I packed.

It is only after a significant time I realized that the intelligence can only be built by dissecting those ideas in quiet and sharing them just reduces my will to absorb them. I feel real intelligence lies in how much we can keep in rather how much we exert.

BRILLIANT READ ! so true

I love the ending with the 6 books with a bit of irony