The Performance of Empathy

Every few months, the timeline fills with candle emojis.

A famous actor dies. A founder we admired passes in an accident. A singer overdoses. Overnight, our feeds become memorial walls: black-and-white portraits, “gone too soon,” a carousel of greatest hits. People say they’re heartbroken. They say they’re shattered. They say they “can’t even.”

I don’t doubt the loss is real for those who knew the person. But for most of us, it isn’t. Not really. We didn’t share dinners, inside jokes, or hospital hallways. What we share is proximity to fame and a platform that rewards visible feeling. So we perform a feeling that isn’t ours to perform.

When the internet stormed with Liam Payne’s death last year, I put a broadcast telling people I didn’t know him, and to my surprise that offended few people.

This isn’t cruelty. It’s culture. We live inside an economy where displayed sentiment is a social currency. Grief has become a dialect everyone is expected to speak.

And I don’t have any problem with people showing grief and care for their favourite people, what I do have a problem with is this pressure of performance.

Parasocial grief, reputational rewards

Two old human systems collide online:

Parasocial attachment — we “know” public figures through relentless exposure, so our brains tag them as familiar.

Reputational heuristics — in tribes, broadcasting care signals that you’re safe to be around.

Put them together and you get what looks like empathy at scale. But it often isn’t empathy; it’s audience management. The timeline places a subtle tax on silence—“so you don’t care?”—and offers a rebate for saying the right things on cue.

And I did post about it but she couldn’t see it for some reason, but most people would comply. Not because they feel it, but because the social math is obvious.

You not posting a story = you must be supportive of what happened

That’s low IQ behaviour.

There is a word for this: performed empathy. It’s what happens when caring becomes a spectacle rather than a relationship.

The circle you actually care about

If we’re honest, most of us carry a small, concentric map of obligation. In the inner ring: parents, siblings, partners, the tiny set of people whose birthdays you remember without a calendar. Farther out: friends-who-are-family. Beyond that: acquaintances, colleagues, strangers with good stories, strangers with tragic stories, the crowd.

My own map is ordinary: my parents, my brother and his family; my future wife and her family. That’s the circle I truly care for. Outside it, my compassion is abstract. I can wish the world well and still refuse to pretend that the death of someone I never met has rearranged my interior life.

That refusal makes people uneasy, because we’ve confused honesty with callousness. But bounded care is not cruelty. It’s an admission of scale. Human attention is finite; real empathy is metabolically expensive. You can’t be present for everyone. If you attempt it, you end up present for no one.

Compassion fatigue, compassion theater

Psychology has long observed two relevant glitches in our moral hardware:

Compassion collapse — we feel deeply for one identifiable person, then less as the numbers rise.

Identifiable-victim effect — a single vivid story elicits aid more than a statistic ever could.

Platforms invert both. They present us with countless identifiable tragedies. The result is fatigue and, eventually, theater: we replay the performative rituals of grief because the real thing would burn us out.

The performance isn’t harmless. A feed full of “devastated” for people you never knew cheapens the language you will need when your father is sick, your friend calls from the ER, your partner stares at the floor and says, “It’s cancer.” The moral account is finite. Spend it on spectacle and there’s less left for the kitchen table.

“I know how you feel” (You don’t.)

Daniel Sloss writes about the death of his little sister and the parade of well-meaning people who told his family, “I know how you feel.” They didn’t. They couldn’t. He wasn’t angry that they cared; he was angry that they pretended to occupy a room they had never entered.

That line should be retired. No one knows how you feel, not even the version of you who felt something similar last year. Grief is specific. It’s shaped by private histories and dumb little details—what time the phone rang, what you were cooking when the doctor called, the half-finished text on a lock screen. To say “I understand” is to claim access to someone else’s interior furniture. You don’t live there.

Better words exist. “I’m here.” “I don’t know what to say.” “I can take tomorrow off and be with you.”

Empathy is not a sentence; it’s a service.

Why public figures pull us into counterfeit mourning

There’s a reason celebrity deaths keep extracting statements from people who barely followed the work.

Familiarity without responsibility. You “knew” them, but they never needed you at 2 a.m.

Safe belonging. Mourning together feels like community with no ongoing cost.

Narrative coherence. A neat story (genius, tragedy, cautionary tale) provides a stage for your identity: “I value art,” “I support mental health,” “I stand against drugs.”

The performance isn’t only cynical. It’s also clumsy longing: we want to belong to something bigger and to feel like good people. But goodness measured in captions is a weak currency. When everything is made public, the public act replaces the private duty.

The ethics of indifference (properly understood)

“I don’t care what’s happening out there” is easy to caricature. So let’s define terms.

Indifference to spectacle is not indifference to people.

Local duty outranks global display.

Honest silence beats dishonest sentiment.

If your friend loses a parent, your job is not to post; it’s to knock on their door with food and empty time. If a famous stranger dies, your job is to decide whether this story genuinely changed you—or whether you are about to counterfeit a feeling because the room expects a performance. If it’s the latter, close the app.

A useful rule: If you couldn’t write the person a letter full of specifics, you don’t get to write a eulogy for the feed.

What to say (and what to stop saying)

Retire

“I know exactly how you feel.”

“Everything happens for a reason.”

The instant carousel of borrowed quotes.

Use instead

“I’m here for the boring parts—laundry, rides, phone calls.”

“I don’t have words, but I can stay on the line.”

“Would it help if I handled [specific task] this week?”

Presence is heavier than prose. Choose the weight.

The public square vs. the kitchen table

The public square wants signals; the kitchen table wants shoulders. The square is loud, fast, and scalable; the table is quiet, slow, and small. A civilization that confuses the two will always mistake seen empathy for useful empathy.

If what you truly care about is your parents, your brother and his family, and the family you’re going to build—then live like it. Design your calendar around them. Allocate your attention like a budget. Refuse to outsource love to captions.

You don’t owe the timeline a performance. You owe your people a life.

A closing honesty

There are countless horrors in the world, and many deserve action. But an endless, ambient concern for everything is not action; it’s paralysis dressed as virtue. You have one life. That can’t be it.

Reserve your grief for the rooms you inhabit. Reserve your language for the moments that require it. Reserve your energy for building what only you can build.

Let the feed mourn the famous. You have a kitchen table to show up at.

if you enjoyed reading this, please do two things:

Share it with someone you admire

Follow me (@aniketium) on X

(if you hate this, please share with all your enemies)

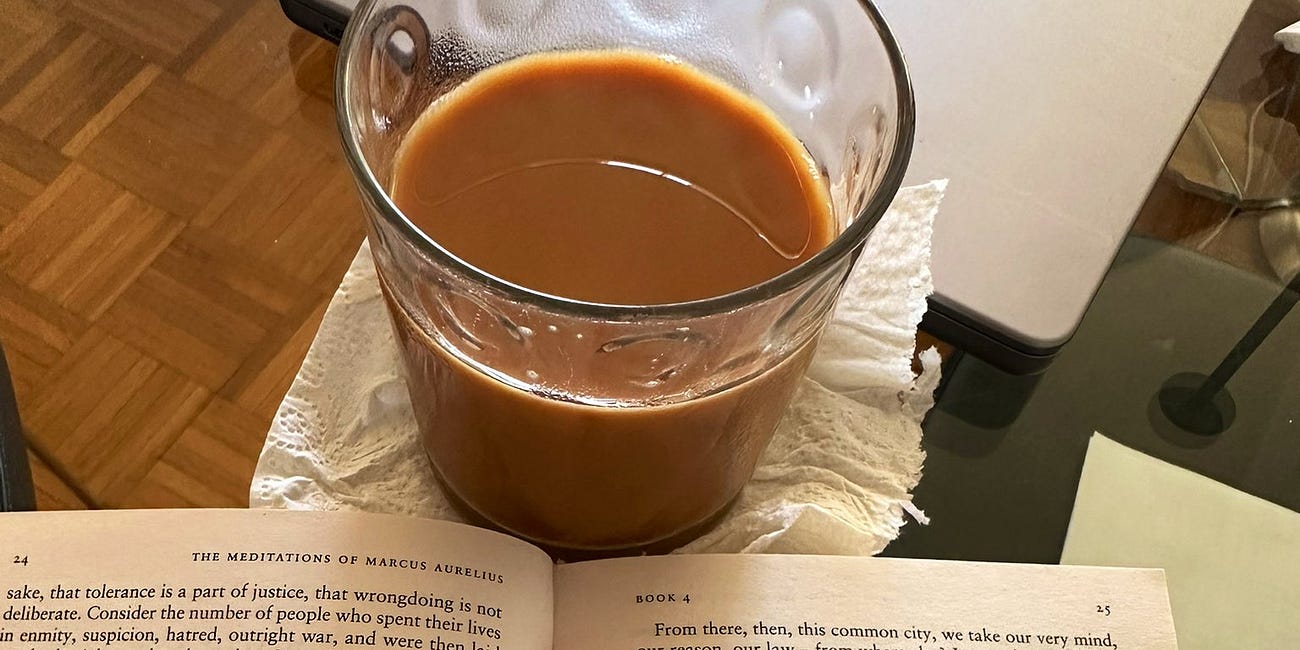

Past piece you might like:

The Performance of Depth

We used to read books quietly, write notes in the margins, and let ideas ferment unseen. Now, the moment we encounter something profound, we turn it into content - a highlight, a thread, a screenshot. We package thought into something postable.