Why we wrap our lives in plastic?

Our obsession with keeping things pristine

A few weeks ago I realized I was behaving like a museum conservator for a bunch of mass-produced objects. My iPhone 16 Pro has an expensive case plus a tempered-glass to protect it, now without those two things it looks beautiful, with those it’s just another phone. The new laptop arrived I wrapped it with a thin skin film and—of course—I am not planning to peel it for a long time.

My father sold his old car when he purchased a new one, the plastic wrap on the music player of the old car was still on. I wonder if the new owner of the old car would pull it off.

Why do otherwise sane people live like curators, guarding “mint condition” at the cost of ease?

I think there’s a hidden ideology here—equal parts psychology, economics, and cultural hygiene. Below are seven lenses that, together, make the case that “don’t let it age” isn’t just a quirk; it’s a system.

1) Loss beats love (and why “newness” becomes an insurance policy)

Behavioral economics gave us two ideas that sit under much of this: loss aversion and the endowment effect. Loss aversion says that a loss hurts more than an equivalent gain feels good. The endowment effect says we value things more because they’re ours, which makes parting with value (a scratch, a ding) feel like a personal loss. Kahneman, Tversky, and Thaler ran the canonical experiments on both phenomena; they found we consistently overvalue what we possess and overreact to potential losses. (Massachusetts Institute of Technology)

Cases, films, films on films: they’re not merely accessories; they’re anti-loss rituals. If a phone’s resale price will drop Rs. 10,000 for a cracked back glass, protecting it is a rational hedge filtered through irrational valuation. We call it “care,” but it’s also a way to mute the pain curve built into our nervous systems.

2) Cleanliness is not next to godliness, it’s next to order

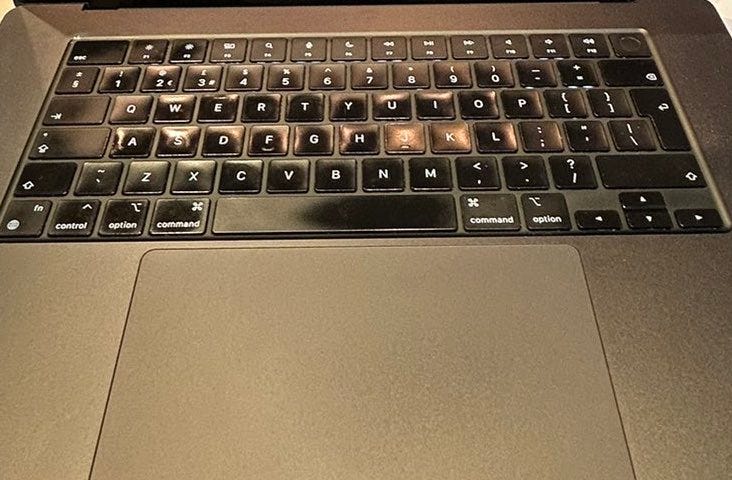

Anthropologist Mary Douglas famously defined dirt as “matter out of place.” Dirt offends because it breaks categories; it signals disorder. In that frame, an oily MacBook keyboard isn’t just worn—it’s category-confused, neither “new” nor authentically “old.” It’s a glitch in the taxonomy. Plastic films, microfiber cloths, and weekly isopropyl sprays restore our objects to their assigned category: pristine. (Wikipedia)

We are hygiene maximalists in our aesthetic lives. Not because microbes threaten us, but because disorder threatens our mental picture of how things ought to be.

3) The status signal of up-to-dateness

The modern consumer’s peacock tail is “latest, unscratched, unyellowed.” A year into ownership, patina on a phone doesn’t read as “stories,” it reads as “laggard.” The object doubles as a status billboard, and status wants sharp edges and no noise. Even when we don’t intend to flex, we’re fluent in the dialect. The pristine thing whispers: I keep up.

Ironically, the market rewards this: listings with “like new,” “NIB,” or “mint” language command premiums, while even small dings tax the price.

Collectors are notorious for valuing pristine boxes more than the thing inside them.

In other categories—coins, ceramics—“cleaned” or “restored” can actually reduce value because originality is the currency; elsewhere, patina pays. Condition is never neutral. (SaleHoo)

4) Industrial design made fragility fashionable

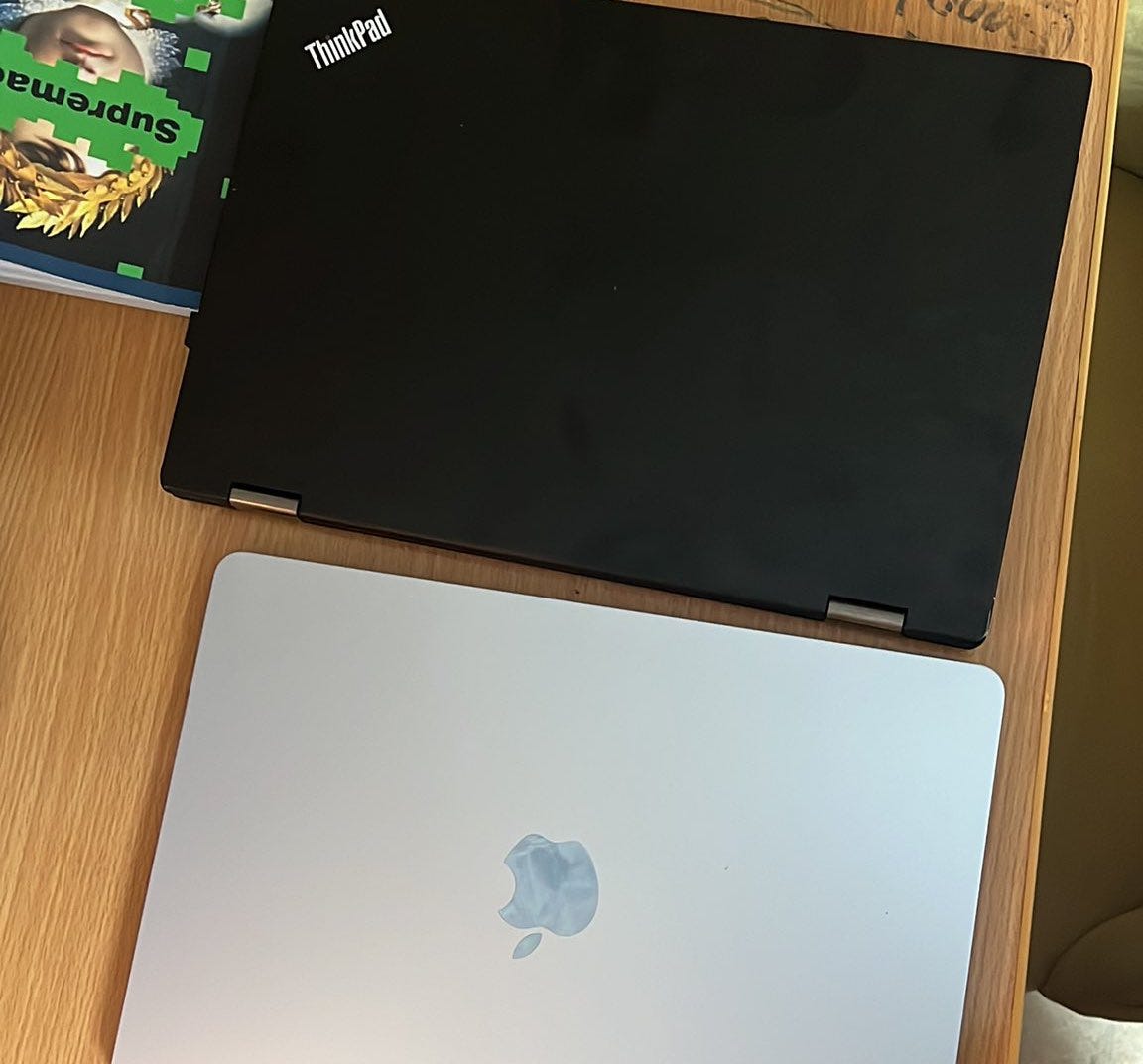

For twenty years, designers have pushed glass, gloss, piano blacks, mirrored plastics—surfaces that photograph well but bruise instantly. The material palette itself coerces care. You wouldn’t baby a brushed-canvas ThinkPad from 2009; you instinctively baby a mirror-finish slab.

Which one are you more likely to clean with a microfiber cloth +isopropyl solution?

There’s a second force: sealedness. As products got harder to repair, the stakes of a scratch went up. You can’t replace just the shell; the whole sandwich is fused. The more irreparable the thing, the more we tent it like a field hospital.

5) Objects as the extended self

Marketing scholar Russell Belk argued that possessions are part of the “extended self.” If that’s true, then a scuff isn’t damage to a tool; it’s a blemish on the border of the self. And because selves, in the social web era, are permanently on stage, the pressure to keep the surface unmarked is high. (JSTOR)

This also explains a puzzle: we’ll obsess over micro-scratches on a phone but tolerate a chipped mug at home. One object sits at the frontier of presentation (pulled out dozens of times a day, photographed against your fingers); the other lives in a private ritual, safe from social optics. Boundary dictates care.

6) The IKEA effect (or, why we’ll baby what we built)

There’s a countercurrent: when we put labor into an object, we value it more. That’s the IKEA effect, participants who folded their own slightly wonky origami priced it closer to expert-made pieces than impartial observers did. Effort glues ownership to identity, which changes how we interpret wear: my scratches can read as authorship. (ScienceDirect)

But many modern objects actively prevent authorship. You can customize a car, but most people don’t. You can’t open your iPhone without voiding its soul. The less we can shape a thing, the more “damage” feels like pure loss, not personal inscription. When authorship is low, protection is high.

7) The minority report: cultures that love patina

There are islands where the opposite ideology rules. Wabi-sabi in Japanese aesthetics celebrates the imperfect and the impermanent, cracked bowls repaired with gold (kintsugi), tea utensils treasured because they carry small signs of time. In the denim world, a pair of raws becomes yours through fades and whiskers; leather goods “come alive” once they darken and scuff. These cultures read age as a story, not a stain. (Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy)

Patina communities argue that, with the right materials, use adds value. A wallet darkens, softens, and literally fits your life. “Patina enhances; wear and tear destroys,” as one leather maker puts it—a distinction industrial design rarely teaches us to see. (Tanner Bates)

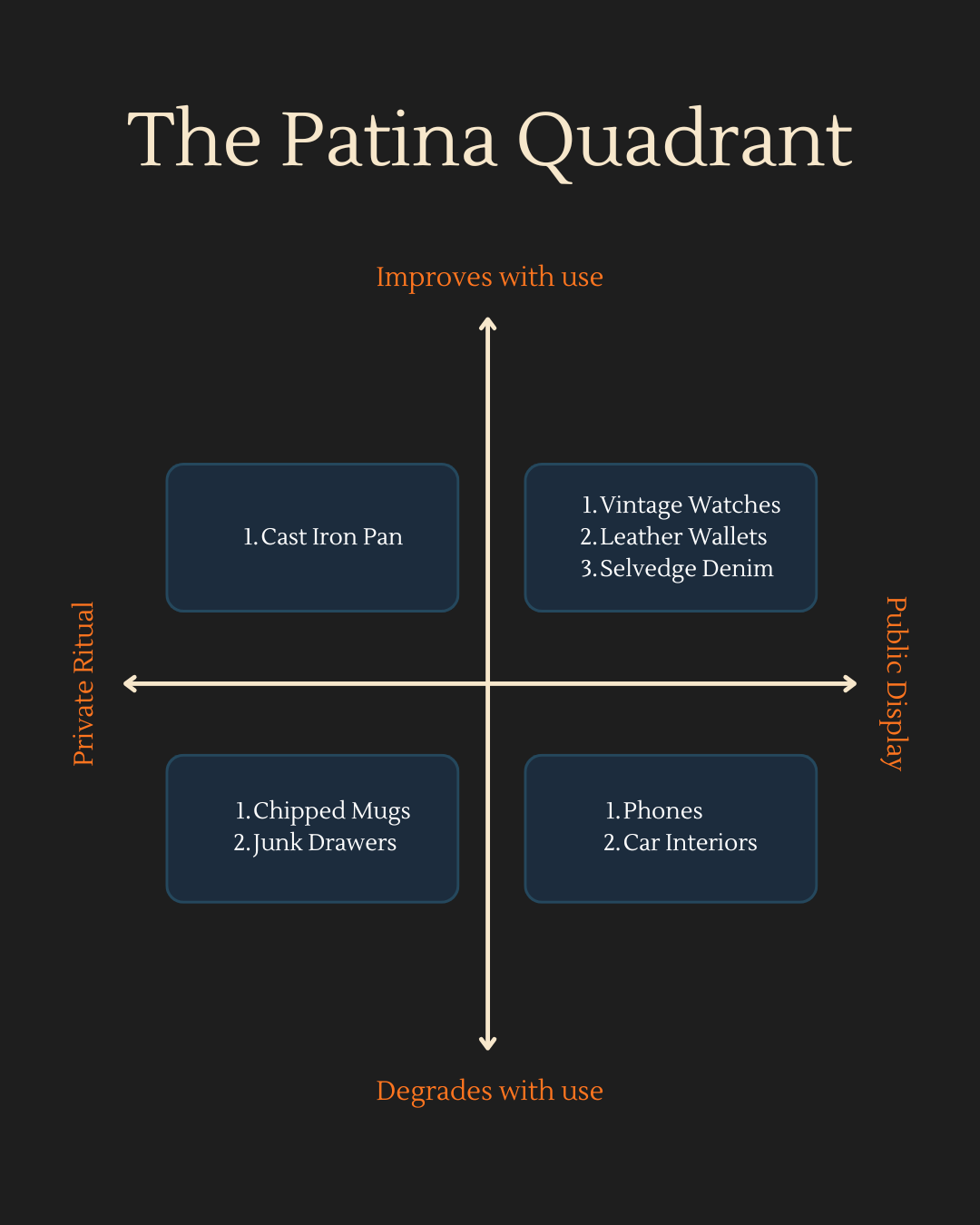

The important move is not “ruin your things.” It’s to realize there are two grammars of value: pristine-value (unmarked originality) and patina-value (storied authenticity). Different categories reward different grammars. Phones prize pristine; heritage boots prize patina. Confusion between grammars is what drives anxiety.

A working model: The Patina Quadrant

Consider two axes:

Material trajectory: Improves with use ←→ Degrades with use

Social exposure: Private ritual ←→ Public display

Why this got worse in the 2010s

Three shifts poured fuel on the pristine fire:

Always-on photography. The feed made surfaces public. Your phone is in more pictures than your face.

Sealed objects. If you can’t maintain or mod, you can only preserve.

Liquidity of resale. The second-hand market is a tap away; depreciation is visible and thus emotionally real. “Like new” becomes a cashable trait; every scratch rings the till. (Collectors and marketplaces codify the premium for condition; in other niches, patina commands a different premium, denim fades threads run “Fade of the Day” like sports highlights.) (SaleHoo)

If you want out of the cult of pristine, you don’t need to swing to nihilism. You can architect for graceful aging.

1) Choose patina-positive materials where you can. Full-grain leather, brass, solid wood, raw denim, stone. These reward exposure and time. They want stories. (The leather and denim literature is basically a love letter to time plus contact.) (carlfriedrik.com)

2) Put authorship back in. Stitch a steering-wheel wrap by hand. Customize your keyboard keycaps. The more labor invested, the more wear reads as authorship rather than damage. That’s the IKEA effect made constructive. (ScienceDirect)

3) Segregate grammars. Keep pristine rules for categories where condition is value (screens, optics); seek patina where function improves with use. Pin the rule to the quadrant, not to your personality.

4) Ritualize restoration, not concealment. Instead of a peel that never peels, learn to polish, condition, oil, and repair. Kintsugi is a metaphor, but also a method: mend to display the story. (Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy)

5) Get honest about risk math. Cases and PPF protect resale; sometimes that’s rational. But when the protection makes the thing worse to use (thick cases, glossy protectors that smear), you’re paying a hidden tax. Walk through the expected, value math with your own usage and resale horizon; don’t outsource it to your anxiety.

The deeper itch: entropy and immortality

The cosmetic war on aging is not confined to things. We fight time in our calendars, faces, and feeds. A pristine object hints at a bigger fantasy: I can pause entropy. Of course you can’t. But you can choose where you’d like your entropy to show up: hidden in foam and film, or visible as stories on the surface of your life.

Wabi-sabi’s invitation is modest: accept that the world is “imperfect, impermanent, and incomplete,” and then learn to see that as beauty. You do not have to adopt the whole aesthetic to borrow the stance. Start with one object you currently baby. Give it permission to age. Watch your mind change as it learns a new grammar of value. (Wikipedia)

If the cult of pristine is about fear, patina is about intimacy. A thing you have lived with long enough to scar—the thing you dared to use—cannot be “like new.” It can be something better: like you.

Further reading (a short shelf)

Kahneman & Tversky on loss aversion and prospect theory; Kahneman, Knetsch & Thaler on the endowment effect. (Massachusetts Institute of Technology)

Mary Douglas, Purity and Danger—dirt as “matter out of place.” (Wikipedia)

Russell Belk on the “extended self” in consumer behavior. (JSTOR)

Norton, Mochon & Ariely on the IKEA effect (and later replications/meta). (ScienceDirect)

Wabi-sabi, Japanese aesthetics, and the cultural case for patina. (Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy)

On patina cultures (leather, denim) as living counterexamples. (Heddels)